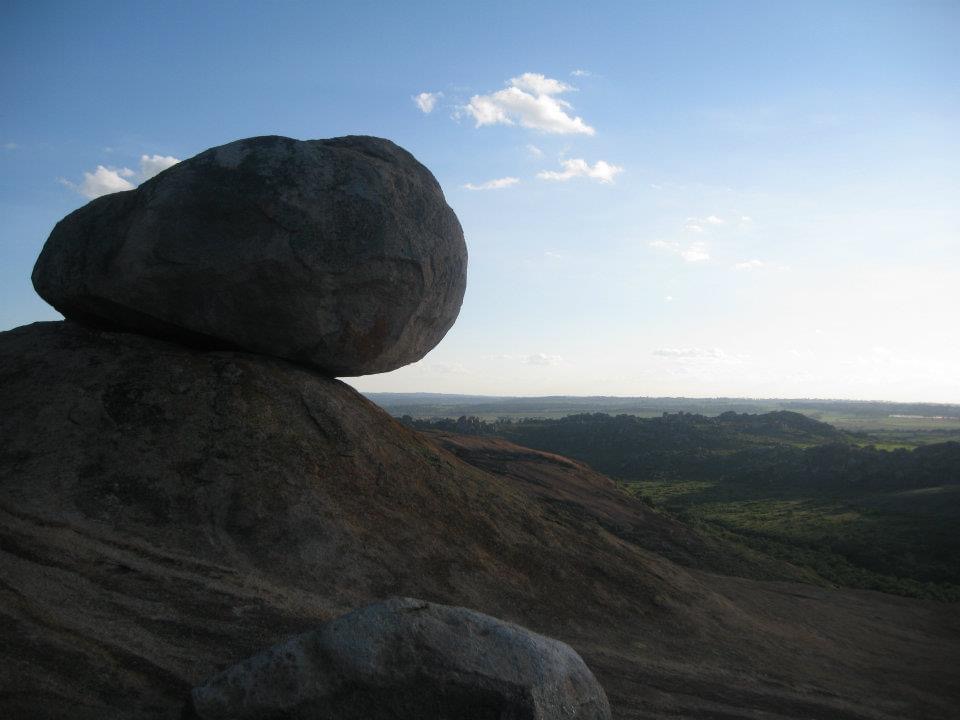

She is a doctor and a health-manager whose tenacity and determination helped St Albert’s hospital remain a solid point of reference in one of the most difficult areas of Zimbabwe (Southern Africa), the rural province of Mashonaland Central, 200km North from the capital, Harare. The area is plagued with poverty, high rates of gender-based violence and child abuse. Julia Musariri is the first of the five “Women in Zimbabwe” we want the world to meet: a woman who was enabled by other women to understand her own potential and act on it, and who is now convinced that empowering women is the key action her homeland needs to progress. She kindly accepted to answer our questions.

by Eleonora Aralla and Loredana De Vitis

Born into a family of smallholder farmers in the Catholic Mission of Monte Cassino in Macheke, Musariri has been a teacher, then a nurse, and finally managed to achieve her objective of becoming a doctor. As Musariri explained, St Albert is a district hospital and «the government pays the salaries of the staff, provide some drugs and pays a part of the hospital’s running costs»; however today her work, aside from planning and implementing disease prevention programmes, also focuses on administration and resources mobilisation (finding funds for medicines, fuel, food provisions, linen, utensils, ambulances, manpower, hospital and farm project equipment), supervision of staff, clinical and income generation projects; in addition, she is involved in «advising the Diocese on health matters, formulating and implementing HIV policies for the country».

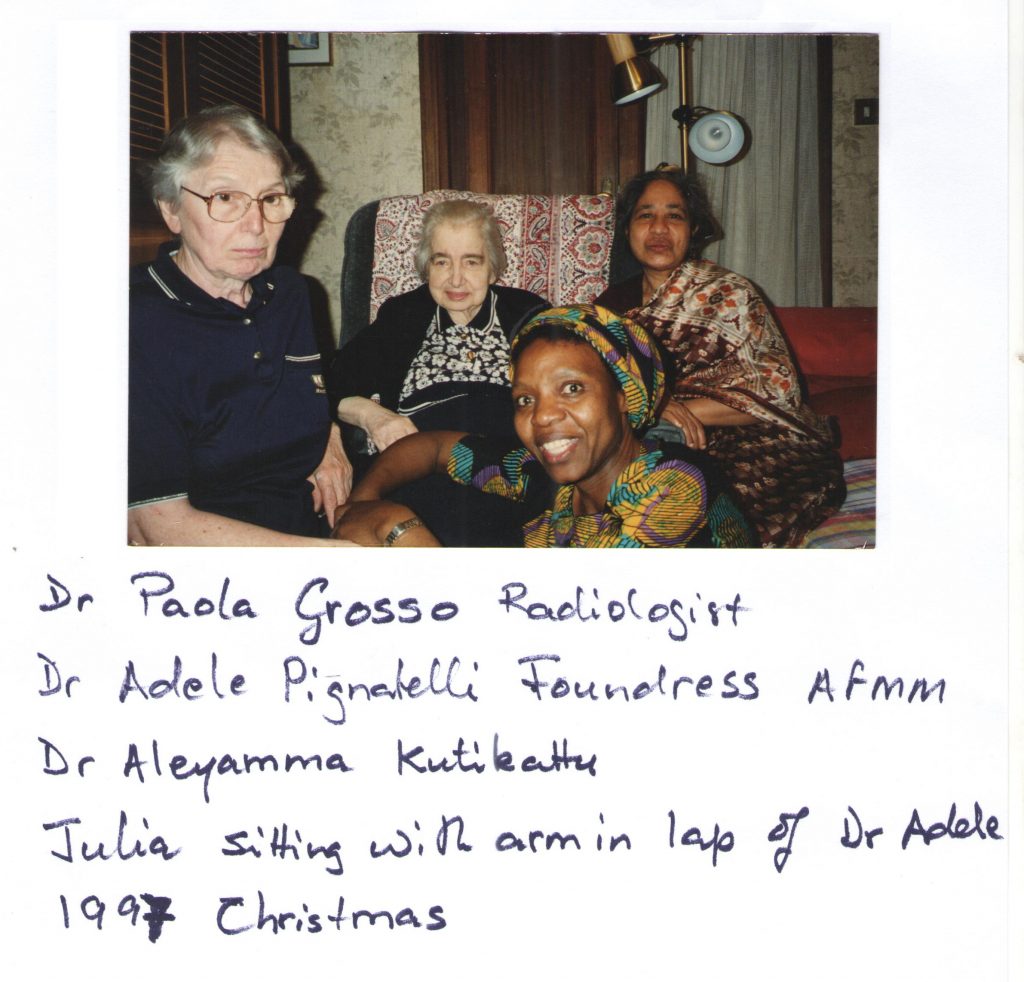

The Diocese is Chinhoyi. Musariri is a member of the AFMM – “Associazione Femminile Medico Missionaria” (Female Medical Missionary Association), within the “International Medical Association”. The organization was founded in Italy in 1954 by Adele Pignatelli – a doctor from Rome member of the Catholic Graduates Movement – with the support of Monsignor Giovanni Battista Montini, who then became Pope Paul VI. The members take the vows of obedience, poverty, chastity and missionary life. It was indeed a meeting with some AFMM’s women that triggered her journey.

«At the age of 17, I had never met a doctor in my life, only a nun nurse at the dispensary who knew how to perform many procedures. One day two Italian nurses arrived at our mission, just to polish their spoken English. I was told that they were going to “All Souls Mission Hospital” to work as nurses, because that is what they were – missionaries. They would be working with female doctors who were already there: Dr Luisa Maria Guidotti, Dr Mariaelena Pezzarezzi and Dr Maria Grazia Buggiani and Sr Caterina Savini, who was a nurse. They belonged to AFMM».

We are at the end of the 1960s, and our attention must focus on one name: Luisa Guidotti (Mistrali). From a family of old noble descent, Guidotti graduates in Medicine and specializes in Radiology; after joining AFMM she is sent to Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe. In 1965 the white minority in the country decided to unilaterally declare independence from the United Kingdom, waging civil war in the country. Guidotti starts working at the “All Souls” Hospital in Mutoko, a rural area north-west of Harare, in 1969. Here, whilst she practices medicine, she raises funds amongst Italian friends and turns the hospital from a few huts into a functional brick walled facility.

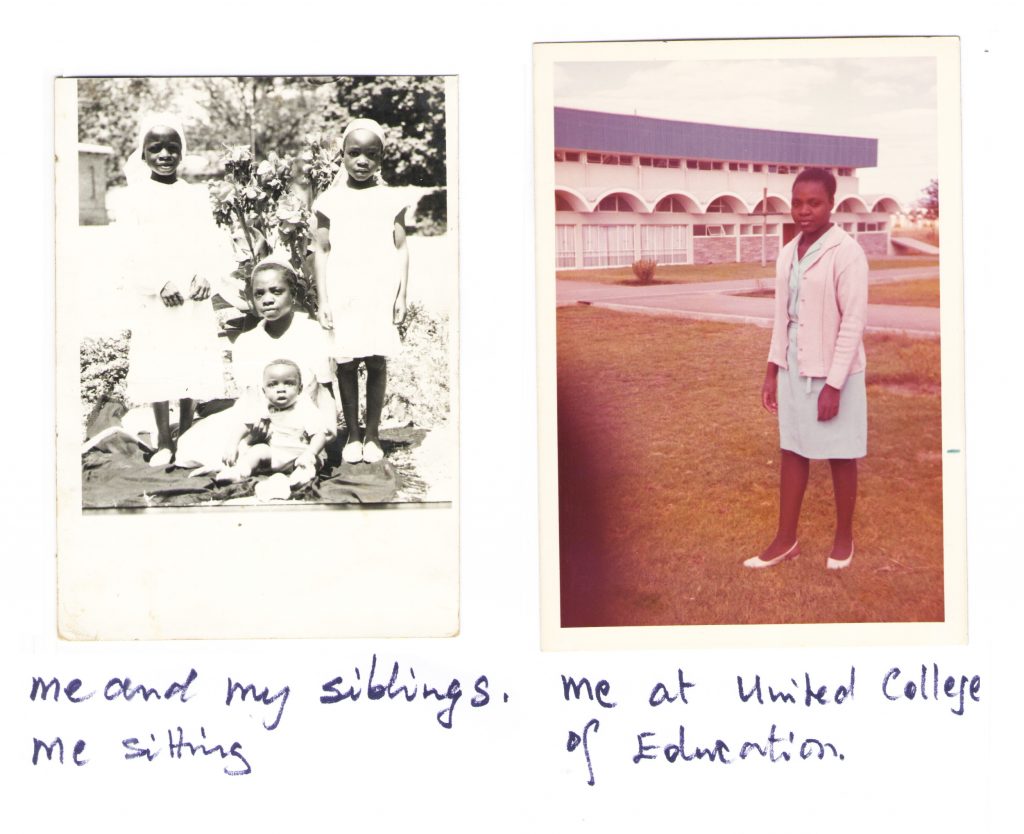

«This group of women, who wanted to give service to my people having left their comfortable homes, intrigued me. The two Marias eventually left for their mission and I lost track of them for a long time. I was an average student in Form Four then. Between 1972 and 1974 I trained as a primary school teacher at United College of Education. I completed my course with flying colours and I got a post for teaching at a mixed race school in Esigodini Matabeleland, where most pupils had a diverse history of harassment in their families. They were a special group of children, who played tricks with teachers. A coloured child – Heath was his name – kept annoying the rest of the class, and would say “who gave me the rudeness I have’ my black mother or my white father”. One day, the boy had pulled out pages from his and his neighbour’s homework book. I got rather angry; I punished him so harshly that afterwards he was very afraid even of just being near me. I regretted my impulsiveness. I asked for forgiveness, but that did not mend my relationship with the child. I then told myself that was not my profession».

The term “coloured” in Zimbabwe defines a particular racial category that was ‘in-between’ whites and blacks in economic, political and social terms. Being of mixed race, in the colonial culture, embodied the dreaded ‘miscegenation’ [1], defiance of racial boundaries that were at the core of colonial society. Until the beginning of the twenty first centuries, the ratio between white males and white females in the colony was three to one; there was therefore an evident problem in terms of sexual relationships, which soon became interracial, with black women often forced by white men to have sex with them.

In the racist eyes of colonial society, African women’s sexuality and its depraved nature lured white men, and the blame was therefore placed on the women, rather than on the predatory acts of the men who would use their power to coerce them. Being a coloured child, therefore, came with a lot of baggage; coloured children, especially in the past, could be seen as not belonging anywhere in society, too white to be ‘fully black’, and too black to be ‘fully white’. And Heath’s sentence perfectly condenses all of this in a few, accurate albeit caricatural words.

It must have been difficult for a young and inexperienced teacher like Musariri to deal with the complex underlying conflicts in that sort of class, which presented challenges that went well beyond any training she could have gotten as a teacher in those years.

«I always wanted to be a nurse, though my parents were not keen. They told me that “Uniforms are white and clean, but the work is very dirty. Besides, nurses are women who are morally depraved”. However, despite my parents’ opposition, I decided to make an application for training as a nurse».

We are in the middle of the civil war. In June 1976, Luisa Guidotti Mistrali gets arrested by the Rhodesian police for having treated a supposed wounded guerriglia fighter, and she risks being executed. She is then released, also thanks to significant pressure by the Vatican, and resumes her work at the All Souls. On the 6th of July 1979, on her way back from accompanying a pregnant woman with a complicated labour to the Nyadiri hospital, she is stopped at a roadblock at Lot and fatally wounded. In 1983 the All Souls was renamed after her, and the beatification process is in progress upon request of the Diocese of Harare.

«It was a tragedy. The poor people of Mutoko lost the only doctor who understood them and was serving them passionately. I resolved I wanted to be part of the AFMM, so that I could serve the sick like she did. “All Souls” was out of bounds, because of the war. Letters for Luisa were taken to Rome by the late Dr Elizabeth Tarira and Dr Rosalba Sangiorgi. As they looked through these letters, they found mine. Meanwhile, I had left teaching and had started training as a nurse at Harare Central Hospital, now Sally Mugabe Hospital, in September 1979, when I received their reply that only said “If you are still of the same mind you can come to Rome”. I resigned from the nursing school and left for Rome, though I had done very well in my exams at school of nursing. I opted to go to Rome to be a member of the AFMM in 1980, on the 3rd March. At home they were euphoric, everyone had voted for the first time and independence from Britain was on the doorstep».

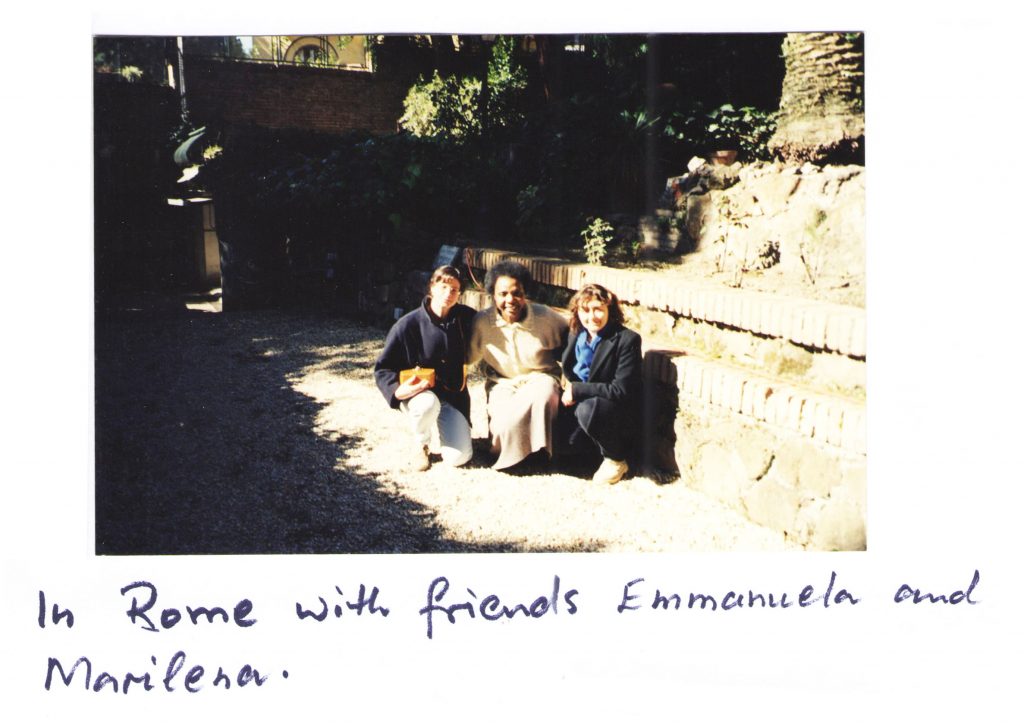

Musariri arrives at the San Giovanni in Laterano Hospital. Three months later she could understand and speak basic Italian.

«In Rome I met the foundress; she said she would have liked me to enter medical school, but I declined. So she sent me to nursing school. After three years, I passed with very good marks. In 1985 I went back to Zimbabwe to work at different mission hospitals; I briefly joined St Albert’s in 1985 before going to Chitsungo Mission Hospital. Working as a nurse gave me great satisfaction and fulfillment, but something was lacking, the ability to help mothers with complicated labour. I could not perform Caesarean sections and we had to transfer all complicated maternity cases to Harare Central Hospital. In 1992, just as I was about to go on annual leave, I was invited to Rome by Dr Adele. She suggested again I get into the Faculty of Medicine. This time I agreed. I was older than any of the other students at Tor Vergata University of Rome. I enrolled for the entrance examination. Among a thousand and more candidates, the university could only take 150; I checked on the result sheet on the notice board, I was 152. But some students renounced, so I was called and I could start training to become a woman doctor».

Were there challenges linked with being a woman?

«In the past medicine was considered a career for males. In our patriarchal society it is still common to think that some professions are only for men; this included the medical one. However, meeting the women doctors of AFMM had a profound influence on me and led me to believe that women and men have equal opportunities. They spurred me on to face the difficulties of language, culture, long hours of travel to university, cold winters and hot humid summers. It was a life changing experience, it completely shifted my mindset. I would like the same to happen for many parents of daughters. Today I can educate young people to pursue their dreams – the sky cannot be the limit anymore, we can go beyond. It is possible for women to outshine anybody».

Mashonaland Central, where St Albert’s operates, is a hotspot for Sexual & Gender Based Violence (SGBV). The Extended Analysis of Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) 2014: Child Protection, Child Marriage and Attitudes towards Violence reported that Mashonaland Central had the highest percentage (50%) of women age 20-24 married before age 18.

Social and health services in the area are limited, and rates of school dropouts high. Education, particularly for girls, is not perceived as a priority as the girls’ role in the traditional culture is mainly a caregiving, subordinate one. Generalized poverty and food insecurity exacerbate the situation; children, especially girls, are forced to drop out early as their families cannot afford school fees and often forced to work. Deep rooted cultural beliefs aggravate the already dire situation, with children’s wellbeing not being prioritized and often becoming victims of neglect and abuse.

CAFOD, the organization Eleonora works for, has been supporting St Albert’s for over 14 years, and it’s currently partnering with the hospital on the Putting Children First programme (now in its 4th phase of implementation), with funds from Caritas Australia and the Australian Government; the intervention focuses on enhancing child rights protection. One of the main objectives of the programme is to positively influence community and household behaviour, challenging harmful cultural and religious beliefs and practices (like early marriages) through widespread targeted capacity building and awareness raising on GBV, gender dynamics, positive parenting and disciplining methods alternative to corporal punishment, particularly of parents of young children, but also of community members at large. Households are also encouraged to use the income to keep their children in school, especially girls, who are the first ones to drop out because of early pregnancies, but also as soon as school fees money becomes difficult to find.

For a girl in Zimbabwe, especially in this area, where sometimes people struggle to have more than one meal a day, getting to her 18th birthday without having gotten pregnant and having completed her secondary school cycle is already an achievement.

How was the experience of studying Medicine in Italy?

«I entered medical school at the age of 29 years. Ten years older than any other student, youngsters who had just come out of high school. It is no wonder they would ask me where I had been, being that old. Italians are patient with those who learn their language. The first friend I made was called Sonia, a red haired and freckled girl, outgoing and very helpful. She introduced me to her 5 friends, Flavia, two Monicas and two Robertas; they adopted me in their group and always shared their notes with me. I did not feel the dreaded isolation and segregation. I worked hard to get my degree in the 6 years required. I was an average student, but that did not worry me. The important thing for me was being able to go back and give service to the many women and children who had never passed through the hands of a doctor in the missions. I thought that if gifted young people like Luisa Guidotti, from a well to do family, could leave all her comforts to come to rural Zimbabwe to take care of our sick people, why could I not do the same? I graduated on the 13th of April 2001. I returned to Zimbabwe to do an internship at Harare Central Hospital. After I completed my two years, I was posted to St Albert’s Mission Hospital».

Here, finally, Musariri is a woman doctor.

«I was now giving medical service. I could perform surgery, especially Caesarean sections. I no longer needed to transfer patients who had complications of labour to Harare. Dr Neela Naha, a gynecologist and obstetrician, also mentored me to handle complex cases. Some colleagues, whilst I was in Italy, had advised me to get married in Italy, get Italian citizenship and stay there. But the truth is I would not exchange what I have been able to do with anything else. I am still at St Albert’s Mission Hospital, doing Out Patients consultations, while the young doctors do the surgeries and all the other work. The Diocese requested me to be its Chinhoyi diocese’s hospitals coordinator as well as being the Medical Superintendent of St Albert’s».

St Albert’s Mission Hospital opened in 1964 and was run by Dominican nun nurses; it initially had 85 beds; in 1985 it became a district hospital, and now has 140 beds. Serving an area of about 134 295 people, every year it admits about 5,000 patients, treats about 40,000 outpatients and delivers about 2,600 babies, in spite of the limited technology available. Moreover, the hospital provides antiretroviral drugs, conducts a home-based care programme to help families care for loved ones with disabilities and chronic illnesses (especially HIV) and pays school fees for hundreds of orphans. In response to the ever increasing economic crisis and subsequent food insecurity, in 2000 the hospital started a farming project (goats, chicken and pigs) to provide nutritious food for hospital patients and, with the sale of the surplus, pay the farm workers.

Your work must have been really challenging given the harsh economic and political context.

«As doctors, we need all the tools of the trade to provide the best solution for the sick. But when I look at our hospital, I get discouraged and disheartened, because the tools of trade are obsolete. My collaborators and colleagues would like to go digital in all spheres: Operation theatre, Radiology, Patient register, laboratory, laundry machines etc etc. But then I see the laundry, with the washing machine and iron roller that don’t even work anymore; the anesthetic machine that the surgeon is constantly complaining about; the mortuary that cannot even manage to keep the bodies cold. The list is endless. The many well wishers we had in the early 2000 for HIV/AIDS programme have switched to other districts; the AFMM has elderly doctors who need care and are unable to fundraise like they did in the past. So we continue to use what any well meaning young doctor would rather not, because the resources do not allow us to acquire new ones. Sadly, we have relied heavily on external donor funding, facilitated by the fact that we had some expatriate missionaries in AFMM working with us who could raise awareness and support St Albert’s cause. Their relatives and friends would fundraise for their work. That is why we still have the machines they bought in the 1990s».

And COVID must have complicated things even further.

«The most immediate effect was a significant reduction of patient flow, particularly pregnant women, and a consequent increase of home deliveries, with all related risks that they entail. We had to close the outpatient department to make room for a small COVID isolation ward, with four beds. The Family Child Health and OutPatients Department now share rooms for consultation. Personal Protective Equipment, including masks, gloves and aprons have been inadequate and insufficient; however we try to continue giving our service».

St Albert’s seems to have a special focus on women’s health (maternal health, cervical and breast cancer screening). Is it a deliberate, strategic choice?

«After Dr Elizabeth Tarira and Dr Neela noted the prevalence of complicated labour outcomes, they came up with the idea of improving maternal health. They built a mother’s waiting home, which accommodated 45 pregnant women, but they had to extend it to the capacity of 105 pregnant women. Women could come and stay near the hospital in the last 2 to 3 weeks of their pregnancies (in order to avoid last minute transport issues ed), for speedy assistance and have timely surgical intervention in time to ensure the wellbeing of both mother and baby. In the district of Centenary there were young women living with HIV and pregnant, vescico-vaginal fistulas, advanced cervical and breast cancers; interventions were needed for all these conditions. Prevention of Mother To Child Transmission was introduced by Dr Tarira with the help of the Italian NGO Cesvi from Bergamo, using single dose Nevirapine (used to treat HIV patients, ed). Takunda, the first baby whose mother volunteered to take the Nevirapine was born Negative; he is now 20 years old. That is an incredible milestone for St Albert’s. The triple therapy for the positive women was introduced in 2004 and we then introduced treatment of their male partners too.Dr Neela did screening of cervical cancer through Visual Inspection with acetic acid (VIA); we have now added a micro-camera with the help of Mr Darrell Ward and Dr Lowell Schnipper from Better Healthcare for Africa – this was a significant a step ahead. Today cervical cancer and breast cancer screening programmes have been rolled out to all districts by the government».

The story of Takunda (‘born free’ in shona, the most common bantu language in the country) can be read here: On the children’s side – Cesvi Onlus – Cooperazione e Sviluppo. In 2001 Cesvi had just started working to fight AIDS in Zimbabwe, one of the most stricken countries. At the time one in three women was HIV-positive, and generally had very scarce chances of survival. Cesvi started the Nevirapine pharmacological trials. Takunda’s mother received treatment and counselling. On May 9th 2001 Takunda was born free of AIDS. [2]

Have you ever thought of leaving?

«My work as a Mission Hospital Doctor in rural Zimbabwe gave me great satisfaction. I feel that God is in it. Otherwise I would have been one of the many women of my age who got married at very young ages and achieved nothing with their primary or secondary education. I also am indebted to my parents who sacrificed a lot of their time and money in order to make a difference with their 13 children. In my retirement I wanted to turn to farming. I have started a poultry project for eggs, a fish project, a goat rearing project, revived the piggery and planted an area of near hectare with caster beans for sale, in order to get some much needed funds for the hospital. The projects are at the start but I am optimistic about them».

In Zimbabwe state pensions are negligible; in most cases they are far from being sufficient to cover basic cost of living, in a country with rampant inflation. It’s very common for people to rely on small sources of extra income like small livestock rearing. That provides valuable additions to their diet (with eggs, chicken meat, goat meat and milk – which is very nutritious) as well as enabling them to sell (or exchange) the surplus and earn something.

You operate daily in a very complex context; which, in your view as a front-line worker, are the main challenges that should be prioritized for resolution? And that, once resolved, would cascade positive results in other areas?

«I personally think if we empower the girl child, we will have gone a long way. Girls of today will be the mothers of tomorrow, in charge of children’s education. They will also be the professional women of the future. It is painful to see young girls becoming mothers due to diverse circumstances. Child rights, particularly the girl child, are a crucial pivot towards achieving the emancipation of the African (Zimbabwean) woman».

If you had the opportunity to let the world know something about your job, what would that something be? Is there a small project that we can contribute to achieving?

«A project that has potential for income generation and sustainability would be an expansion of the current fish project or the poultry project, where we can market the proceeds – eggs and fish – and, with the money, we can meet some of the expenses we are failing to meet today. The fish and poultry are doing well and promising to be helpful. We want to be self-sufficient. On the medical side, we are in need of a modern multi-parameter patient monitor for our operation theatre, especially for C-sections».

Donations can be sent to the bank account:

Stanbic – Minerva Branch

account number 9140001107576

BIC-code: SBICZWHX

or through Better Healthcare for Africa:

Donate to BHA – Better Healthcare for Africa

[1]

The Chronicle, 12th February 2000

‘Joshua Cohen walks down memory lane’, Parade, August 1999.

Robert J.C. Young, Colonial Desire: Hybridity in Theory, Culture and Race, (Rutledge, London, 1995, p. 5)

[2]

On the children’s side – Cesvi Onlus – Cooperazione e Sviluppo

Mother and child | World news | The Guardian