Julia Musariri è una medica e una manager sanitaria la cui tenacia e determinazione sono state essenziali perché il St Albert’s hospital restasse un solido punto di riferimento in una delle aree più complesse dello Zimbabwe (Africa meridionale). Parliamo della provincia rurale del Mashonaland Central, 200 chilometri a nord della capitale Harare, caratterizzata da profonda povertà e un alto tasso di violenza di genere e abusi sui minori. La dottoressa Musariri è la prima delle cinque “Women in Zimbabwe” che vogliamo presentare: una donna che, grazie ad altre donne, ha compreso e saputo sviluppare il proprio potenziale, e che è ora convinta che l’empowerment delle ragazze sia l’azione chiave perché lo Zimbabwe possa progredire.

di Eleonora Aralla e Loredana De Vitis

Nata in una famiglia di agricoltori nella missione cattolica di Monte Cassino a Macheke, Musariri è stata prima un’insegnante, poi un’infermiera, per raggiungere infine l’obiettivo di diventare una medica. Oggi il suo lavoro va ben al di là dell’esercizio della professione. Come ci ha spiegato, il St Albert è un district hospital, «il governo paga gli stipendi del personale, fornisce alcune medicine e finanzia una parte delle spese di gestione dell’ospedale», ma lei si occupa – oltre che della pianificazione e dello sviluppo di programmi di prevenzione – di amministrazione e di fundraising (per l’acquisto di medicine, carburante, forniture alimentari, biancheria, strumentazione, ambulanze, personale, attrezzature per i progetti sia sanitari che agricoli), di supervisionare lo staff, di progetti clinici e di ideare azioni per ottenere ulteriori introiti necessari. Inoltre è consulente della Diocesi «su questioni di salute e per la formulazione e lo sviluppo di politiche anti-HIV per l’intero territorio».

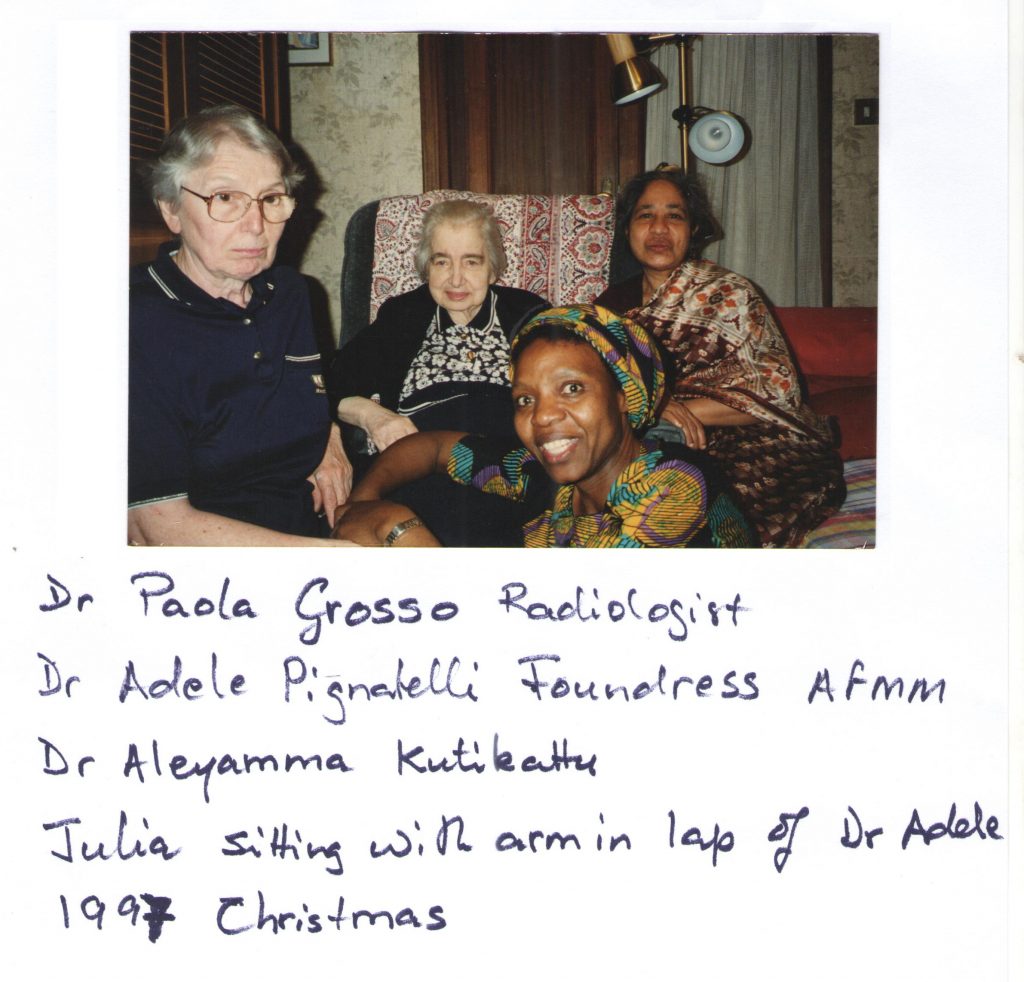

La Diocesi in questione è quella di Chinhoyi. Musariri fa parte della AFMM – “Associazione Femminile Medico Missionaria”, all’interno della “International Medical Association”. L’associazione venne fondata in Italia nel 1954 da Adele Pignatelli, una medica romana che faceva parte del “Movimento dei laureati cattolici”, con il supporto di Monsignor Giovanni Battista Montini, il futuro Papa Paolo VI. Chi entra a far parte dell’associazione fa voto di obbedienza, povertà, castità e vita missionaria. Proprio l’incontro con alcune donne della AFMM ha dato a Musariri il la per cominciare il suo percorso.

«All’età di 17 anni non avevo mai visto un medico, solo una suora infermiera al dispensario, che conosceva come fare molte procedure. Un giorno nella nostra missione arrivarono due suore, venute solo per migliorare il loro inglese. Mi fu detto che erano destinate all’“All Souls Mission Hospital” per lavorare come infermiere, erano missionarie. Avrebbero lavorato con le dottoresse che erano già lì: Luisa Maria Guidotti, Mariaelena Pezzarezzi e Maria Grazia Buggiani, e con suor Caterina Savini, che era infermiera. Erano della AFMM».

Siamo alla fine degli anni 1960. Di famiglia d’antica origine nobiliare, Luisa Guidotti (Mistrali) si era laureata in Medicina e specializzata in Radiologia; dopo essersi unita alla AFMM fu inviata in Rhodesia, l’attuale Zimbabwe. Nel 1965 la minoranza bianca aveva deciso unilateralmente di dichiarare l’indipendenza dal Regno Unito, dando il via alla guerra civile. Nel 1969 Guidotti aveva cominciato a lavorare all’ospedale “All Souls” a Mutoko, area rurale a nord-ovest di Harare. Qui aveva anche raccolto fondi tra gli amici italiani per trasformare l’ospedale da un insieme di capanne a una struttura di mattoni.

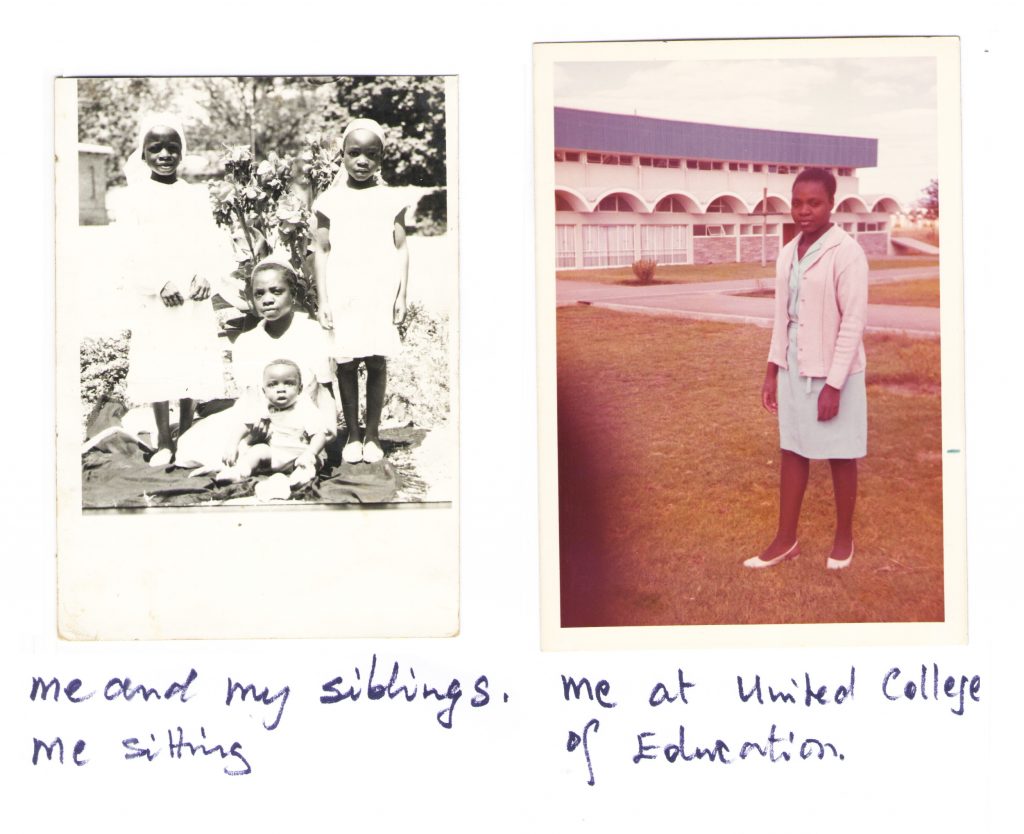

«Queste donne, che avevano lasciato le loro confortevoli case perché desideravano servire la mia gente, mi affascinarono. Al tempo frequentavo la prima superiore, con voti medi. Delle due missionarie persi a lungo le tracce. Tra il 1972 e il 1974, studiai allo United College of Education per diventare insegnante di scuola primaria. Dopo aver completato il corso col massimo dei voti cominciai a lavorare in una scuola mixed race a Esigodini in Matabeleland, dove la maggior parte degli studenti aveva alle spalle storie di abusi in famiglia. C’era un gruppo particolare di bambini che faceva dispetti alle insegnanti. Un bambino coloured [meticcio, ndr] – si chiamava Heath – continuava a disturbare il resto della classe, dicendo “chi mi ha dato la mia maleducazione, mia mamma nera o mio papà bianco?”. Un giorno strappò alcune pagine dal suo quaderno dei compiti e da quello di un compagno. Mi arrabbiai molto. Lo punii così severamente che, da quel momento, il ragazzo fu molto spaventato persino a starmi vicino. Gli chiesi scusa, ma non bastò per recuperare la relazione tra noi. Mi dissi che quello non era il mestiere per me».

Il termine “coloured” in Zimbabwe fa riferimento a una categoria razziale che stava ‘tra’ bianchi e neri, in termini economici, politici e sociali. Essere di razza mista, nella cultura coloniale, significava incarnare la temuta ‘mescolanza’ [1] che sfida i confini tra le razze. Fino all’inizio del Ventunesimo secolo, la proporzione tra uomini bianchi e donne bianche nella colonia britannica era di tre a uno, il che rappresentava un problema in termini di relazioni sessuali: queste divennero presto interrazziali, e le donne nere venivano spesso abusate dagli uomini bianchi.

Vista attraverso la lente razzista della società coloniale, la sessualità depravata delle donne africane provocava gli uomini. La colpa degli abusi era, quindi, attribuita alle donne. Un bambino coloured nasceva per questo con un grosso peso sulle spalle, i bambini coloured non avevano praticamente alcun posto nella società: troppo bianchi per essere neri, troppo neri per essere bianchi. La frase del piccolo Heath lo esprime in poche, accurate, beffarde parole.

Deve essere stato difficile per un’insegnante giovane e inesperta come Musariri affrontare i complessi sottesi conflitti di quel genere di classe: si trovava a dover affrontare sfide ben al di là di qualunque formazione ricevuta.

«Ho sempre voluto diventare infermiera, anche se i miei genitori non ne erano entusiasti. Mi dicevano “Le uniformi sono bianche e pulite, ma il lavoro è molto sporco. Dietro le apparenze, le infermiere sono donne moralmente depravate”. Comunque, nonostante l’opposizione dei miei, decisi di candidarmi a un corso per infermiere».

Nel pieno della guerra civile, nel giugno 1976, Luisa Guidotti Mistrali venne arrestata dalla polizia rhodesiana per aver curato un presunto guerrigliero e rischiò l’esecuzione, evitata anche grazie alle pressioni del Vaticano. Ma il 6 luglio 1979, tornando dal Nyadiri hospital, dove aveva accompagnato una donna con un travaglio complicato, venne fermata a un posto di blocco a Lot e ferita a morte. Anni dopo, nel 1983, le è stato intitolato l’ospedale All Souls e, su iniziativa della Diocesi di Harare, avviato il processo di beatificazione.

«Fu una tragedia. La povera gente di Mutoko aveva perso l’unico dottore che la capiva e se ne prendeva cura appassionatamente. Decisi che volevo far parte dell’AFMM, per poter servire i malati come faceva lei. L’“All Souls” era irraggiungibile a causa della guerra in corso. Le lettere indirizzate a Luisa furono portate a Roma dalla dottoressa Elizabeth Tarira e dalla dottoressa Rosalba Sangiorgi. Tra queste, anche la mia. Nel frattempo avevo abbandonato l’insegnamento e avevo iniziato il programma di formazione per diventare infermiera presso l’Harare Central Hospital, ora Sally Mugabe Hospital. Nel settembre 1979 ricevetti la loro risposta. Diceva solamente: “Se sei sempre dello stesso avviso, vieni a Roma”. Lasciai il programma e partii per Roma, nonostante avessi avuto risultati eccellenti agli esami sostenuti fino a quel momento. Decisi di andare a Roma per per far parte dell’AFMM nel 1980, il 3 marzo. A casa erano euforici, tutti avevano votato per la prima volta e l’indipendenza dalla Gran Bretagna era alle porte».

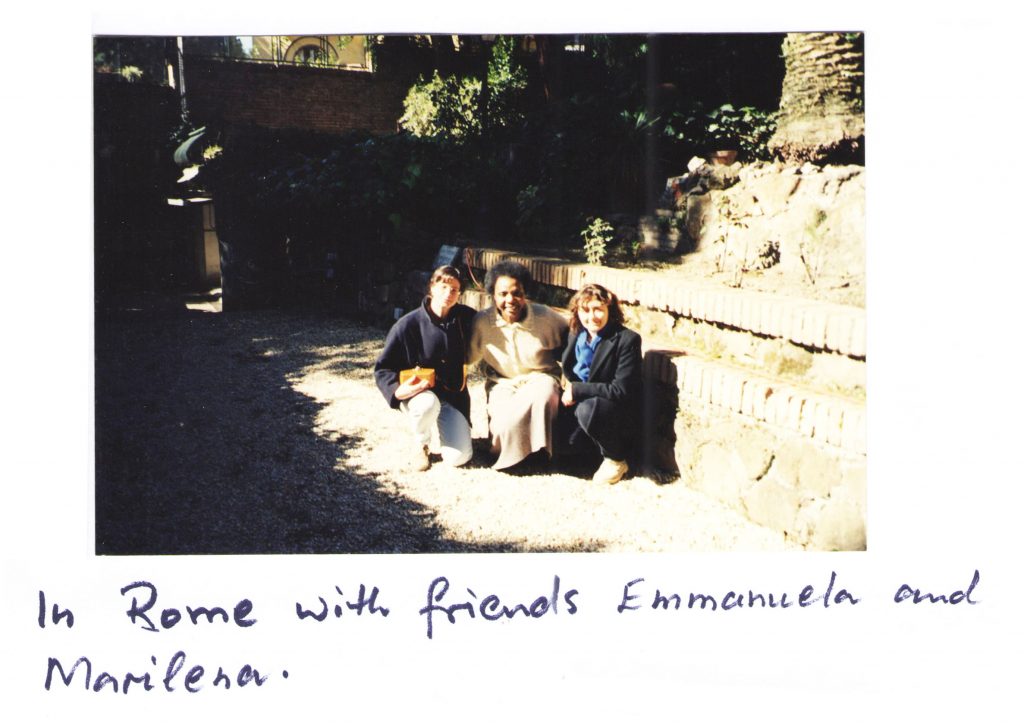

Musariri giunse così all’ospedale San Giovanni in Laterano. Tre mesi più tardi capiva e parlava un italiano-base.

«A Roma incontrai la fondatrice. Mi disse che le sarebbe piaciuto che entrassi a Medicina, ma rifiutai, perciò mi mandò alla scuola d’infermeria. Dopo tre anni, passai gli esami a pieni voti. Nel 1985 tornai in Zimbabwe per lavorare in vari ospedali missionari; passai solo un breve periodo al St Albert’s nel 1985 prima di andare all’ospedale missionario di Chitsungo. Fare l’infermiera mi dava grande soddisfazione, ma mi mancava qualcosa: la capacità di aiutare le madri con travagli complicati. Non potevo effettuare tagli cesarei e dovevamo trasferire tutti i casi di travaglio con complicazioni all’Harare Central Hospital. Nel 1992, poco prima di andare in ferie, fui invitata a Roma dalla dottoressa Adele, che mi suggerì nuovamente di studiare Medicina. Questa volta accettai. Ero più grande di qualunque altro studente all’Università di Tor Vergata. Mi iscrissi all’esame d’accesso. Tra mille e più candidati, l’università poteva accettarne solo 150. Controllai i risultati sulla bacheca. Ero la numero 152, ma alcuni studenti rinunciarono. Perciò fui chiamata e così iniziai la mia formazione per diventare medica».

Ci sono state difficoltà dovute al fatto d’essere una donna?

«In passato la medicina era considerata una carriera maschile. Nella nostra società patriarcale è ancora comune che si pensi ad alcune professioni come esclusivamente maschili. La medicina è una di queste. Tuttavia incontrare le mediche dell’AFMM aveva avuto su di me una profonda influenza, e mi aveva spinta a pensare che donne e uomini avessero le stesse opportunità. Mi avevano spronata ad affrontare le difficoltà linguistiche, culturali, le lunghe ore di viaggio verso l’Università, gli inverni freddi e le estati umide. Fu un esperienza che mi cambiò la vita, modificando completamente il mio modo di pensare. Mi piacerebbe che succedesse lo stesso ai genitori di molte ragazze. Oggi ho la possibilità di educare persone giovani a perseguire i propri sogni. Il cielo non è più il confine, possiamo andare oltre. È possibile, per le donne, fare meglio di chiunque altro».

Il Mashonaland Central, dov’è collocato il St Albert, è un vero e proprio hotspot per la cosiddetta Sexual & Gender Based Violence (SGBV). I dati dello studio “Extended Analysis of Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) 2014: Child Protection, Child Marriage and Attitudes towards Violence” riportano il Mashonaland Central come la zona con la più alta percentuale di donne (50%) tra i 20 e 24 anni sposate prima dei 18 anni.

I servizi sanitari e sociali nell’area sono limitati, e la percentuale di abbandono scolastico molto alta. Lo studio, in particolare per le ragazze, non è considerato una priorità, dal momento che nella cultura tradizionale il ruolo di una donna è essenzialmente subordinato e di cura. La povertà generalizzata e l’insicurezza alimentare contribuiscono a esacerbare la situazione; i bambini, specialmente le bambine, sono costretti ad abbandonare presto gli studi e spesso a cominciare a lavorare, perché le famiglie non possono affrontare i costi delle tasse scolastiche. Le credenze arcaiche, ancora profondamente radicate, aggravano ulteriormente il quadro: il benessere dei bambini non è una priorità, e spesso sono vittime di incuria e abusi.

Il CAFOD, l’organizzazione per cui lavora Eleonora, supporta il St Albert da 14 anni, ed è attualmente partner dell’ospedale nel programma Putting Children First (ora nella quarta fase di implementazione), che utilizza fondi messi a disposizione da Caritas Australia e dal governo australiano; gli interventi mirano al miglioramento della protezione dei diritti dell’infanzia. Uno degli obiettivi principali del programma è quello di avere un’influenza positiva sul comportamento delle famiglie e della comunità, sfidando le credenze e le pratiche come i matrimoni precoci attraverso la diffusione della conoscenza e della consapevolezza sulla violenza di genere, le dinamiche di genere, la genitorialità positiva e i metodi alternativi alle punizioni fisiche. Si lavora principalmente con i genitori dei bambini più piccoli, ma anche con i membri della comunità più in generale. Le famiglie sono inoltre incoraggiate a utilizzare i propri introiti per far studiare i bambini e soprattutto le bambine, le prime ad abbandonare la scuola a causa delle gravidanze precoci oppure semplicemente quando il denaro per le tasse scolastiche non c’è.

Per una ragazza in Zimbabwe, specialmente in quest’area, dove a volte si deve combattere anche soltanto per avere più di un pasto al giorno, compiere 18 anni senza aver avuto una gravidanza e avendo completato il ciclo di studi secondario è già un risultato.

Come è stato studiare Medicina in Italia?

«Entrai a Medicina all’età di 29 anni. Dieci anni più grande di qualunque altro studente, ragazzi che erano appena usciti dalle superiori. Non c’era da meravigliarsi che mi chiedessero cosa avessi fatto fino a quel momento. Gli italiani sono pazienti con chi sta imparando la loro lingua. La mia prima amica si chiamava Sonia, una ragazza coi capelli rossi e le lentiggini, espansiva e sempre pronta ad aiutare. Lei mi presentò alle sue cinque amiche: Flavia, due Monica e due Roberta; mi adottarono nel loro gruppo, condividevano sempre gli appunti con me. Non sentii il tanto temuto isolamento né la segregazione. Lavorai sodo per ottenere la laurea nei sei anni previsti. Avevo voti medi, ma la cosa non m’impensieriva. L’importante per me era poter tornare e prestare servizio alle moltissime donne e ai bambini che non avevano mai visto un medico nella missione. Pensavo che se giovani persone dotate come Luisa Guidotti, che veniva da una famiglia agiata, potevano lasciare le comodità della propria casa per venire nello Zimbabwe rurale a prendersi cura dei nostri malati, perché io non potevo fare altrettanto? Mi laureai il 13 aprile 2001. Tornai in Zimbabwe per fare il tirocinio presso l’Harare Central Hospital. Completati i due anni, fui mandata al St Albert’s».

Finalmente, Musariri divenne medica.

«Finalmente prestavo servizio come medica. Ero in grado di effettuare operazioni chirurgiche, specialmente tagli cesarei. Non avevo più bisogno di trasferire pazienti con complicazioni ad Harare. La dottoressa Neela Naha, una ginecologa specializzata in ostetricia, mi preparò alla gestione di casi complessi. Alcune colleghe, mentre ero in Italia, mi avevano consigliato di sposarmi, prendere la cittadinanza italiana e rimanere. Ma la verità è che io non scambierei ciò che ho con nient’altro. Oggi sono ancora al St Albert’s, mi occupo dei pazienti ambulatoriali, mentre i dottori più giovani si dedicano alle operazioni chirurgiche a al resto del lavoro. La Diocesi di Chinhoyi mi ha chiesto di diventare la coordinatrice dei loro ospedali, e sono la Sovrintendente Sanitaria del St Albert’s».

Il St Albert’s Mission Hospital è nato nel 1964 ed è gestito da suore domenicane. Aveva inizialmente 85 posti letto. Nel 1985 è divenuto un district hospital, e ora ha 140 letti; è al servizio di un’area con una popolazione è di circa 134.295 persone. Ogni anno ospita 5mila pazienti, ne cura 40mila e assiste la nascita di circa 2.600 bambini malgrado la limitata tecnologia disponibile. Nonostante innumerevoli difficoltà, l’ospedale fornisce farmaci antiretrovirali, porta avanti un programma di cure a domicilio per aiutare le famiglie a occuparsi di familiari disabili o con patologie croniche (soprattutto HIV) e paga le tasse scolastiche per centinaia di orfani. Per far fronte alla sempre crescente crisi economica e alla conseguente insicurezza alimentare, nel 2000 l’ospedale ha avviato un progetto di allevamento (capre, polli e maiali), in modo da provvedere ai pasti per i pazienti e, con il ricavato delle vendite del surplus, pagare i lavoratori del progetto.

Il suo lavoro deve essere davvero arduo in un contesto così difficile dal punto di vista economico e politico.

«Da medici, abbiamo bisogno di tutti gli strumenti del mestiere per fornire le migliori soluzioni di cura ai malati. Ma guardare il nostro ospedale è demoralizzante, perché gli strumenti del mestiere sono obsoleti. I miei collaboratori e colleghi vorrebbero finalmente usare tecnologie digitali in tutti i campi. Ma in lavanderia la lavatrice e il rullo da stiro non funzionano più; il chirurgo si lamenta costantemente del macchinario per l’anestesia; nella camera mortuaria non si riescono nemmeno a conservare i cadaveri (per mancanza di elettricità, ndr). La lista è infinita. I molti benefattori che avevamo negli anni 2000 per i programmi a sostegno della prevenzione e cura dell‘HIV/AIDS sono passati ad altri distretti; le mediche dell’AFMM sono anziane e hanno bisogno di cure e non sono più in grado di raccogliere fondi come facevano in passato. Perciò continuiamo a utilizzare quello che qualunque altro dottore benintenzionato preferirebbe non usare, perché le nostre risorse non ci permettono di acquistare nuovi strumenti. Purtroppo abbiamo fatto troppo affidamento su fondi di donatori esterni, grazie alla presenza di missionarie espatriate dell’AFMM che lavoravano con noi, che potevano far conoscere e supportare la causa del St Albert’s. I loro parenti e amici raccoglievano fondi per il loro lavoro. È per questo che abbiamo ancora macchinari degli anni ’90».

E il COVID deve aver complicato ulteriormente le cose.

«L’effetto più immediato è stata una riduzione significativa del flusso di pazienti, in particolare donne in gravidanza, e il conseguente aumento di parti in casa, con tutti i rischi che questi comportano. Abbiamo dovuto chiudere gli ambulatori per far spazio a un piccolo reparto COVID, con quattro letti. Il reparto di Salute Infantile e Familiare e gli ambulatori al momento sono nello stesso spazio. I dispositivi di protezione personale, incluso le mascherine, i guanti e i grembiuli sono inadeguati e insufficienti; tuttavia noi cerchiamo di continuare a fornire il nostro servizio».

Il St Albert sembra avere una particolare attenzione per la salute delle donne: salute delle madri, screening per il cancro della cervice e del seno e altro. Si tratta di una scelta deliberata, strategica?

«Dopo aver notato la prevalenza di travagli con complicazioni, le dottoresse Elizabeth Tarira e Neela ebbero l’idea di migliorare la salute materna. Costruirono una casa maternità, che poteva ospitare fino a 45 donne in stato avanzato di gravidanza, ma presto dovettero estenderne la capacità a 105. Le donne potevano venire a stare vicino all’ospedale nelle ultime due o tre settimane, e avere così rapido accesso all’assistenza e alla sala operatoria in caso di bisogno, per assicurare il benessere sia della madre che del bambino. Nel distretto di Centenary c’erano giovani donne con fistole vescico-vaginali, tumori mammari e al collo dell’utero in stato avanzato; c’era bisogno di intervenire su tutti questi problemi. La prevenzione della trasmissione materno-infantile dell’HIV fu introdotta dalla dottoressa Tarira grazie al supporto dell’ONG italiana Cesvi di Bergamo, usando una dose singola di Nevirapina. Takunda, il primo bambino la cui madre si era offerta volontaria per l’assunzione di Nevirapina, nacque negativo all’HIV; adesso ha 20 anni. Quella fu una pietra miliare per il St Albert’s. La terapia tripla per le donne positive al virus fu introdotta nel 2004, e successivamente fu introdotto anche il trattamento per i loro partner. La dottoressa Neela si occupava dello screening per il cancro al collo dell’utero attraverso l’ispezione visiva con acido acetico; recentemente abbiamo anche aggiunto una microcamera, con l’aiuto di Darrell Ward e del dottore Lowell Schnipper della fondazione Better Healthcare for Africa, cosa che ha rappresentato un enorme passo avanti. Attualmente i programmi di screening per il tumore al seno e al collo dell’utero sono stati allargati dal governo a tutti i distretti».

La storia di Takunda (‘nato libero’ in shona, la più diffusa lingua bantu del paese) si può leggere qui: On the children’s side – Cesvi Onlus – Cooperazione e Sviluppo. Nel 2001 il Cesvi aveva appena iniziato a lavorare nella lotta all’AIDS proprio in Zimbabwe, uno dei paesi più colpiti. In quegli anni una donna su tre era HIV-positiva, e generalmente aveva possibilità di sopravvivenza molto scarse. Il Cesvi cominciò le sperimentazioni farmacologiche con la Nevirapina. La madre di Takunda fu sottoposta al trattamento e monitorata. Il 9 maggio 2001 Takunda nacque libero dall’AIDS. [2]

Ha mai pensato di cambiare mestiere?

«Il mio lavoro come medica in un ospedale missionario mi ha dato grandi soddisfazioni. Ci trovo Dio dentro. Altrimenti sarei stata una delle tante donne della mia età che si sono sposate da giovanissime e non hanno combinato nulla con la loro istruzione primaria o secondaria. Sono anche in debito con i miei genitori, che hanno sacrificato il loro tempo e il loro denaro per cercare di fare la differenza per i loro 13 figli. Dopo la pensione vorrei dedicarmi all’agricoltura. Ho dato vita a un progetto di allevamento di pollame per la produzione di uova, di pesce e capre, ho rimesso in piedi quello di maiali; ho piantato un’area di circa un ettaro con fagioli per la vendita, in modo da ottenere fondi, di cui l’ospedale ha estremo bisogno. Questi progetti sono in fase iniziale, ma sono ottimista».

In Zimbabwe le pensioni statali sono bassissime; nella maggior parte dei casi sono a malapena sufficienti a coprire i costi base della vita, vista la rampante inflazione. È molto comune che si faccia affidamento su piccoli introiti extra come i piccoli allevamenti di bestiame. Qualcosa che può apportare significativi miglioramenti della dieta quotidiana (uova, carne bianca, latte di capra – molto nutriente), come pure consentire vendite o scambi per guadagnare qualcosa.

Lei lavora quotidianamente in un contesto molto complesso; dal punto di osservazione di una lavoratrice in prima linea, quali sono le principali battaglie da combattere? Quelle che, una volta risolte, potrebbero avere a cascata ulteriori risultati positivi?

«Sono convinta che, se lavoriamo sull’empowerment delle bambine possiamo fare molta strada. Le ragazze di oggi saranno madri domani, incaricate dell’educazione dei figli. E le professioniste del futuro. È doloroso vedere giovani ragazze divenire madri, a causa di diverse circostanze. I diritti dei bambini, specialmente delle bambine, sono lo snodo cruciale per raggiungere l’emancipazione delle donne africane e (e zimbabuane)».

Se dovesse indicare qualcosa di importante da far conoscere del suo lavoro, quale sarebbe? C’è un piccolo progetto che possiamo contribuire a realizzare?

«Un progetto che potrebbe potenzialmente generare introiti ed essere sostenibile sarebbe l’allargamento dell’attuale allevamento ittico o di quello di pollame, i cui prodotti possono essere venduti – uova e pesce – e, con quel denaro, possiamo pagare alcune delle spese che non siamo in grado di coprire al momento. Dal punto di vista medico, abbiamo bisogno di un moderno monitor multiparametrico per la sala operatoria, specialmente per i tagli cesarei».

Donazioni possono essere inviate tramite bonifico bancario a:

Stanbic – Minerva Branch

account number 9140001107576

BIC-code: SBICZWHX

o attraverso Better Healthcare for Africa:

Donate to BHA – Better Healthcare for Africa

[1]

The Chronicle, 12th February 2000

‘Joshua Cohen walks down memory lane’, Parade, August 1999.

Robert J.C. Young, Colonial Desire: Hybridity in Theory, Culture and Race, (Rutledge, London, 1995, p. 5)

[2]

On the children’s side – Cesvi Onlus – Cooperazione e Sviluppo

Mother and child | World news | The Guardian