Eleonora Aralla is a wonderful woman, of a beauty the way I think of it, beyond all stereotypes, of body and mind, personality, verve, pride, ability of act and react. I introduce her to you because, through our relationship, I can tell you about a country that is not on the daily news agenda but deserves to be: Zimbabwe.

Ex British colony, it is situated in Southern Africa, bordering, amongst others, Mozambique and South Africa; its parks preserve a stunning nature and the official definition of ‘Republic’ [does not] conceal a very hard dictatorship. While I write this post, looking for news on Google, I find ‘Men eaten after having been attacked in his home by hyenas’, ‘Tragic accident in a mine’, ‘Bishops; appeal for reconciliation and unity’ and, on Amnesty International’s webpage, “Authorities must use bail hearing to release journalist Hopewell Chin’ono”.

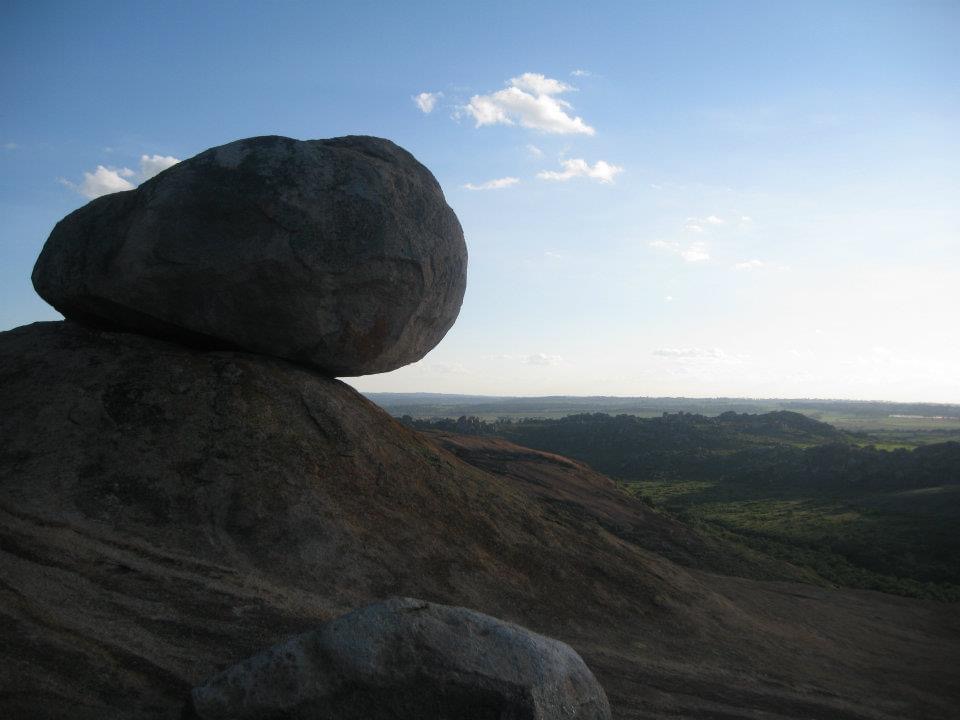

In shona (in the karanga dialect), the most common bantu language in the country, Dzimba-dza-mabwe means ‘house of stone’; the breath-taking Victoria Falls mark the border between Zambia and Zimbabwe; Danai Gurira’s parents – the actress in The Walking Dead – are from Zim; some scenes from ‘White Hunter, Black Heart’ by Clint Eastwood were shot on Lake Kariba in Zimbabwe. Just some examples.

Let me go back to Eleonora.

When somebody denigrates Facebook, I think about what happened between her and me. Let’s take a step back, to 2017, when, just before my son Giovanni was born, I bumped into a post by the Mayor of my city, Lecce, in the heel of the Italian boot. It was a letter by a woman fellow citizen, talking about how she had left years before but kept regular track of local politics, and expressing her joy at the ‘little miracle of hope’ his election had been.

Some doubts, a memory, a couple of investigations and I realize that that citizen is her. Because years before, I am not sure how, I had discovered her blog ‘la chica con la maleta’ (‘the girl with the suitcase’, not currently visible), and I had really liked it. But above all, way before, during my first years of work, when some of my journalist female colleagues used to call me ‘pulciotta’ (chicklet), I had met her in person, feminist activist at University, in Lecce, when the issue wasn’t a very common topic for debate. At least not in today’s terms, so widespread and simple, as demands that need the general public’s attention. We are talking about the early 2000s.

Then, the re-encounter on Facebook and the conversation along the Lecce-Harare line (they are in the same time zone) around children and books, politics and, at some point, about Africa. Eleonora is one of the women that compelled me to express myself correctly when talking about Africa. Africa is a continent, a huge continent to which we owe much of our wellbeing. And when talking about Africa one must express herself well, accurately.

After your BA in Humanities with a thesis in Political Philosophy about ‘Human rights and justice without borders’, a Masters in Sustainable Development, various courses on Monitoring and Evaluation and Gender, the choice. How? Why?

«I was eager to put in practice what I had learnt, I wanted to get to know different cultures, shuffle my point of view on reality and learn something new about myself and the world around me. When I was about 17, I happened to read about Marianella Garcia Villas, ‘the lawyer of the poor, the sick, the forgotten’, whom I discovered years after was a symbol of the fight against government’s abuse in El Salvador. That woman and her tragically sad story remained with me. When it came to choosing a destination, Zimbabwe seemed like a ‘natural’ choice: it is the country of origin of the man who became my husband, who is Zimbabwean of British origin and now adoptively Italian. Besides, it is a country that, for who works in the development sector, offers good living conditions for families, it is considered a ‘family posting’, since it presents low levels of socio-political and health risks, with respect to countries like Afghanistan or Sudan. I have been in Zimbabwe since 2011 and I wish to stay there because it gives me and my family, amongst other things, the privilege of perspective».

And what is that?

«It is the daily chance of appreciating the essential, of living a simplified existence. In Zimbabwe there are no malls, nor it is reached by Amazon; you can find only a couple of kinds of yogurts or cheese at the supermarket – for example. Sometimes, for weeks, you cannot find flour or bread (for people that, like us, can afford them), and so we eat more rice, or potatoes, or eggs, whatever is available. Sometimes there is no running water; once we went 18 days with no power. Nobody makes a tragedy of it. These ‘discomforts’, which I live as an opportunity, are made up for by endless green nature, all kinds of animals coming to visit our garden (like the blue headed lizards or the turacos), by myriads of stars that look so close, while the dark African night hangs over you – and they remind you how few, simple things are the ones that count and that us human beings are just precarious, fleeting guests».

In Zimbabwe you work for CAFOD, officially defined “the Catholic international development charity in England and Wales”. What is your job for them about?

«People generally think that this job is all about offloading bags of grains from a truck or dig boreholes with your bare hands, whilst, in reality, humanitarian work is made up of the stratification of innumerable layers. Hyper-simplifying, I work at the intersection between the donors’ (EU, UN, national aid agencies) strategic planning and priorities and the NGO’s vision and programmes. Right now I support CAFOD’s programme teams in the different sectors (agriculture, WASH, social protection, child rights) in identifying sources of institutional funding, I coordinate the design and the writing of the project proposals, ensuring all quality standards (both financial but also around the safeguard of the beneficiaries) and contractual laws are adhered to. I also work to strengthen the capacity of the local partners we work with in terms of resource mobilization, development of project proposals, grant management to enable them, in time, to access funds directly and manage them on their own, without our help».

Sorry if I trivialize: give me an example of a typical day at work.

«I arrive at my office after avoiding countless crater-like potholes, commuter omnibus packed with people that shoot left and right in traffic, rickety bikes, children in uniform who walk to school on the side of the road, sellers of small handcrafts, street kids begging for food or small change. I sit down and spend a lot of time at my computer. I read emails, check deadlines, look at my calendar. We got a grant from UNICEF for a provision of WASH in schools! Great, we will organise a start up workshop with our local partner and I will oversee the familiarisation of our teams and our partner’s with the donor’s rules and standards, ensuring everyone agrees on the content and logic of our proposal, for us to be able to soundly put it in practice on the ground, to help the words on a sheet become a borehole drilling activity, a training on menstrual hygiene, an advocacy campaign… At the end of the workshop, I go home to my kids».

All this in complex political environment. Which, however, I don’t often see featuring in the agenda of the international media.

«Globally Zimbabwe is not a strategic priority, neither political nor economic».

Just to give you two examples, apart from the journalist cited on the Amnesty webpage, Hopewell Chin’ono, it is worth reading this Al Jazeera interview of Tsitsi Dangarembga: https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2020/11/16/qa-tsitsi-dangarembga (and the related proposed articles).

Shall we dwell into the humanitarian situation?

«There is a rampant financial crisis, with the newly introduced local currency exponential devaluation throwing public sectors workers into poverty and practically making middle class disappear. Climate change is exacerbating already harsh environmental conditions (particularly in certain areas of the country), with recurrent droughts, floods, and cyclones. An increasingly erratic rainy season is heavily affecting planting and harvesting patterns, leaving households at the mercy of food insecurity and malnutrition. Children, who sometimes walk for several kilometres to get to school, can get to the point of fainting on the way simply because they just don’t eat enough calories. Communities are often plagued with child abuse and Gender Based Violence (GBV) and early pregnancies are common. The health system is beyond collapse: public clinics and hospitals lack everything, from paracetamol to cannulas, not to mention electricity and water; doctors are in almost constant strike. The education sector is also in critical conditions, with teachers on strike and the level of education rapidly dropping».

With even more serious consequences for women.

«As usual. Let me give you a practical example. In Zimbabwe girls often do not have access to sanitary pads of any kind. When they do, maybe thanks to the support of an NGO, there is the issue of underwear, often they do not have any. Let’s say they had access to the menstrual cup. Well, they do not have running water at home nor at school. The result is that, on average, girls miss four, five days of lessons a month, which often contributes to school dropout, early marriages, and pregnancies as well as engagement in commercial sex work as a strategy to survive. In this scenario, organisation like mine (both international and local) work to support vulnerable groups, provide tools and means to generate income and livelihoods, but obviously this is not enough. I think Zimbabwean women and men are an extraordinary example of resilience, but perhaps, also, of resignation».

What is it like to work as a non-Catholic in an organization that is Catholic by its very statute?

«CAFOD is the direct expression of social and ‘progressive’ Catholicism, which is the environment that inspired my professional choice as an adolescent. Although I am not a Catholic anymore, I share the values of solidarity, dignity and compassion that inspire CAFOD’s work. The organisation does not impose the Catholic faith on anyone, neither employees (I have colleagues of all faiths) nor partners or beneficiaries. Our partners of choice are the local Caritas, but we also work with several secular partners in the most disparate programme areas».

A few months ago you came back to Lecce, because of COVID.

«At the end of March the pandemic exploded in South Africa and all the projections were pointing towards the same direction for Zimbabwe. The outcome would have been devastating, had that projection been accurate, given the situation of the health system in the country. International flights were being cancelled all over the world and so, in agreement with the Head of Global Security we decided to be pre-evacuated. We got onto the last flight that left Harare before everything was closed. Thankfully, and for reasons that are not entirely clear even to the experts, COVID has so far spared Africa, or at least has hit less violently. So, we are heading back home at the end of the year, hoping to be able to go pick up where we left off».

How has your political position changed during the years?

«During my University years, when I was in the Equal Opportunities Committee of a student association, I wouldn’t even have called myself a feminist. The word feminism still made people turn up their nose, we were trying to make gender issues palatable to the wider student public – including many female students, for who – I remember well – ‘gender discriminations no longer existed’. Besides, my activism was rather improvised, it had a ‘gut’ quality to it, and it was based on my direct experiences of discriminations and violence, together with a wider yearning for justice for the ‘category’ I belonged to. My professional life brought me to what I thought was a different place, only to realize that the gender issue is pivotal in the work I do. So now I finally call myself a feminist, but one in the making. I study and, most of all, learn on the ground, in a context that is far away from the predominant Western culture, in which I come into contact with people of all origins, geographical and cultural».

You are one of the right people, I think, to talk about how racism and feminism intertwine.

«Feminism cannot exempt itself from dealing with inequalities that overlap in the existence of women with diverse cultural and social identities. Quoting Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, inequalities linked with the colour of someone’s skin are not disjointed from others that have to do with class or sexual orientation, and all of these are not just ‘the sum of all parts’. Personal life experience of each woman counts. That is why, for me, feminism must be intersectional. In the words of Fannie Lou Hamer, activities of colour for civil and women rights, ‘nobody’s free until everybody’s free’. It is a vision that is very close to my own way of feeling and to my own experience. It is also important to pay close attention to the way certain issues are addressed and ‘solutions’ are proposed. Cultural contexts in which we operate need to be accurately analysed, and different positions must be respectfully acknowledged, trying to avoid the white saviour stereotype. Gender issues need to be tackled in the single different contexts and in the framework of the various intersecting discriminations. There are no helpless women to be saved, but women that are the heart of a complex discourse, whose culture needs to be respected and whose strengths need to be enhanced and celebrated».

Conscious of our privileged position, with ‘Women in Zimbabwe’ (from January 2021) Eleonora and I decided to tell you something more about women that live and work in Zimbabwe, starting with five stories we find significant. At the end of each story, we will try to explain what we can do to help and how to do it. This way we can give a new meaning to our privilege.